I don’t think her mother would have to send an email out to the parents, warning them of her fashion choice.

I’ve gotten so many comments like this in reaction to my blog about the sexism intrinsic in the NYT piece “What’s So Bad About A Boy Who Wants To Wear a Dress,” that I am going to respond in a post.

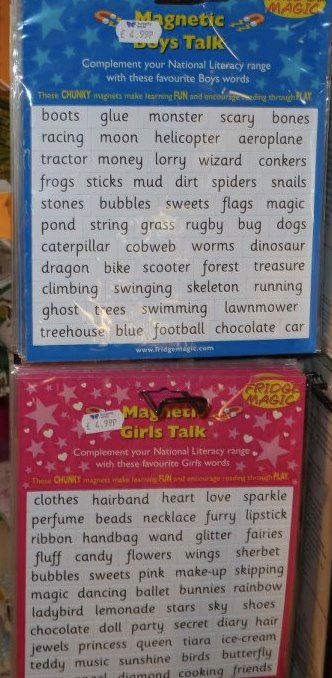

No parent would send such an email because gender-pressure/ sexism against girls is more accepted. (I’ve been calling it “subtle” as well but, really, how subtle are Target’s gender-segregated aisles?) I wish we could write emails, but people would think we’re crazy, because people don’t think they’re sexist; they don’t think sexism exists and so, unfortunately, an email won’t work. Much of my whole, damn blog is dedicated to just pointing out sexism. Sexism exists, and it exists everywhere, and it’s often celebrated and not questioned by smart, progressive, educated parents. One commenter just sent me a link to this blogger praising the NYT piece with: “girls who waltz into previously male-dominated arenas are almost uniformly applauded.”

It’s just not true. God, I wish it were.

I do have some tactics to suggest for parents to deal with sexism/ gender-pressure, but before I even go into that, it’s really important not to let this issue devolve into: who has it worse, girls or boys? When we create rigid gender boxes for our kids, everyone loses out. Everyone. This is about raising healthy, happy, children, helping their brains grow so that they can reach their potential. Defending a boy for wearing a dress and a girl for wearing a Spider-Man T is the same thing, not an oppositional thing. And it’s a much deeper issue, too, because most girls today are in a place where we can’t defend them, because they won’t put on a Superhero shirt. Obviously, the same is true about boys in dresses, even if it’s only playing dress up.

Here’s the thing: Most kids like to play with dolls, but we label them “dolls” or “action figures.” Most kids enjoy pushing objects on wheels, but we sell them either trucks or babystrollers. As I wrote, most kids would have fun painting their nails if they thought it was OK to do so. Most kids, while playing outside will pick up sticks and occasionally poke each other with them. Most parents respond to that same act with “Boys will be boys” or “Sweetie, stop that! You’ll hurt yourself and rip your dress.”

There’s this one part in the NYT article that I excerpted in my first post:

Still, it was hard not to wonder what Alex meant when he said he felt like a “boy” or a “girl.” When he acted in stereotypically “girl” ways, was it because he liked “girl” things, so figured he must be a girl? Or did he feel in those moments “like a girl” (whatever that feels like) and then consolidate that identity by choosing toys, clothes and movements culturally ascribed to girls?

While the writer doesn’t go on to explore that, the point of my first post was that adults can’t even begin to decode without first recognizing the gender-Jim Crow kidculture that our children are immersed in.

It kind of reminds me of when I had an eating disorder, and I told my therapist I felt fat. She told me that fat was not a feeling. “What?” I said, shocked. “Do you feel anxious?” she asked me. “Lonely? Frustrated?” It took me years to decode fat talk. Though I don’t say or think “I feel fat” anymore, I hear other women use those words all the time, eloquent grown-ups with large vocabularies. What are they trying to say?

Here are some ways, daily, that I decode gender talk, because though an email won’t work, saying the right thing at the right time sometimes does. Here are three main groups parents need to speak up to, even if it’s awkward, even if you feel like a bitch.

Teachers

At a parent conference, my favorite teacher glowed when he told me that my daughter played soccer like a boy. “What does that mean?” I said. “She’s good,” he said. “She goes right after the ball.” We then got in a discussion about my daughter’s behavior, and how she loved kickball, but that at recess the kids were starting divide up: girls do monkey bars, boys do kickball. I asked the teacher if he would encourage the kids to mix it up. I offered my help. When I was a parent volunteer on a field trip, the naturalist asked the kids to split in two groups, so the teacher said: “Boys on one side, girls on the other, that’s easiest.” So what if it’s “easiest” at that moment? Moves like that, in the long run, hurt kids. A teacher would never dream of saying: “White kids here, kids of color there.” I suggested a different kind of split and luckily, the naturalist backed me up, pairing them up herself.

Doctors

When my kids go to the doctor, they’re often called princesses, told their clothing is pretty, and when they leave, they’re offered a princess sticker. I asked the workers at the office not to offer the princess stickers, though it’s still a struggle because most characters who are girls are princesses. When people tell my kids they are pretty or their clothing is pretty, I change the subject, “XX is a great artist, tell the nice woman what you drew on your way over.” Or “XX loves to read, tell her about Charlotte’s Web.” As I’ve written about quite a bit, these are adults trying to be nice, trying to break the ice with kids. Help here is often appreciated when delivered the right way. Rebecca Hains just posted about taking her son to the dentist, and here is how she tried to intervene:

“Hello!” said the dentist. “I just want to count your teeth today,” he said reassuringly. “And let’s make sure they’re all boy teeth, okay?”

As my son smiled and opened his mouth per the dentist’s request, I said, “Gee, I’m pretty sure they’re all people teeth, doctor.”

The denist began the exam but seemed to have missed my point. “Let’s see. Boy tooth… boy tooth… boy tooth…”

I didn’t like where this was going. In a gentle effort to redirect his script, I asked a playful question: “Hmm…Are you sure none of them are puppy teeth?”

“Puppy teeth? No… But, uh, oh!” In a voice of mock concern, he asked, “Is this one a girl tooth?!?!”

Smiling at my son as naturally as possible, I said in a bright, upbeat tone, “Gee, it could be!” (Meaning: and there would be nothing wrong with that!)

The dentist frowned and furrowed his brow. “No, no,” he said, “this is a boy tooth. You are a boy. You don’t have any girl teeth! Phew.”

It’s hard. It’s awkward because we can’t send an email like “GET A CLUE. BE OPEN. BE KIND.” And the fucked up thing is, people are often trying to “be kind” when they push stereotypes on kids. Except when they’re not…

Other kids

My six year old was at a party yesterday with a jumpyhouse and she told me that a girl there said to her (the little sister of the party girl, no less) “You can’t come in unless you’re a pretty princess.”

“What did you tell her?” I asked. Hoping for something like “I’m brave and strong and can jump over your three-year old butt.”

My daughter said, “I told her I was Ariel.”

Ariel, ugh. But at least my daughter thought it was weird, noticed it enough to talk with me about it after. A tiny victory, but something.

If I were there, of course, I would’ve smiled and said something like, “What about Merida? She can shoot arrows and turn her mom into a bear!” And I bet they both would’ve laughed and gone in. Little kids are the easiest to intercede on, and I do it all the time.

Balancing Jane asked this question as well: what can parents do on a daily basis?

So first I would say: Do something! Speak up.

I started a blog, that helps a lot. Now I have a whole community of people and resources to help break out of gender boxes.

I seek out books and movies that feature heroic females. This blog has many recommendations and lists. A Mighty Girl is a great resource. And remember, it’s important to read books and show your sons movies featuring strong girls. The myth out there, reinforced by parents terrified their boys will wear dresses, is that girls will see movies about boys but boys won’t see movies about girls. (Nothing to do with training, nothing to do what Hollywood offers them…) Take a leadership role in proving that untrue.

I’m writing a middle grade book about strong girls. That helps, too.

As the mom of three girls, I schedule playdates with boys and invite boys to birthday parties.

Last night, I put my three year old in Superman pajamas, called her Supergirl, and said, “You’re so strong! You can fly!” We played for a while before bed.

Little things are big things.

Emails won’t work, so we’ve all got to be creative here. Tell me your ideas. Even better, report your acts.